History it seems has tried to repeat itself.

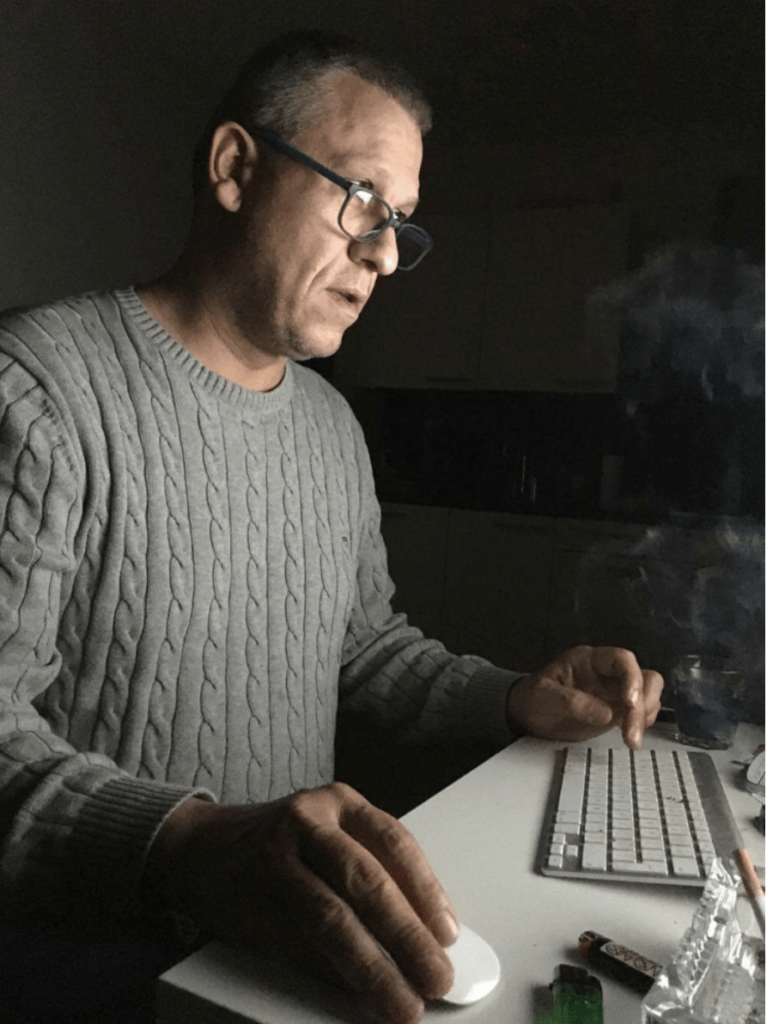

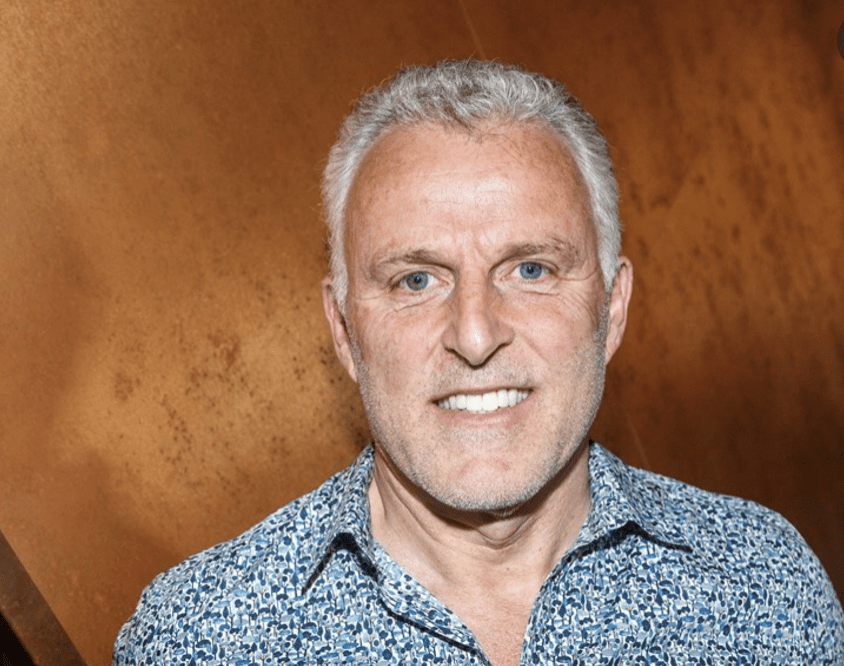

Yesterday in the Dutch city of Amsterdam there was a assassination attempt on a crime blogger, the victim is Peter r de Vries who is widely-known for his investigative work on the Dutch criminal underworld.

A Dutch crime reporter who had been the target of death threats was shot and badly injured in Amsterdam on Tuesday evening.

Peter R de Vries was shot in the capital as he left a television studio where he had appeared as a guest.

Arrests

Police said three people were arrested – two in a car on a motorway and one in Amsterdam.

According to Amsterdam’s police chief, one of those arrested is “probably” the suspected shooter.

Police didn’t give further information on the arrests or a possible motive for the crime.

Dutch caretaker prime minister Mark Rutte said the shooting was “shocking and inconceivable”.

“It is an attack on a courageous journalist and therefore an attack on the freedom of the press which is so essential for our democracy and our rule of law,” he told a news conference.

Fighting for his life

The 64-year-old journalist and TV presenter is “fighting to stay alive” according to Femke Halsema, the mayor of Amsterdam.

De Vries is well-known in the country for his role in several criminal cases, having regularly appeared as a spokesman for victims or in the close circle of key witnesses.

He has received a number of death threats during his career.

Witnesses on Tuesday heard five gunshots and saw that the journalist had been shot in the head, public television NOS reported.

The Security Minister Ferdinand Grapperhaus went to the National Security and Counter-Terrorism Agency (NCTV) in The Hague in the evening to “discuss” the case.

“This is a dark day, not only for the people close to Peter R. de Vries but also for the freedom of the press,” Grapperhaus told journalists.

“We want journalists in the Netherlands to be able to carry out any investigation that needs to be carried out in freedom. This freedom has been seriously undermined tonight,” he added.

“Journalists in the European Union must be able to investigate crime and corruption without fearing for their safety,” said the EU representative of the Committee to Protect Journalists, a US-based press freedom organisation.

Career in crime reporting

De Vries has worked for several publications in the past and has been an independent crime journalist since 1991.

He investigated the murder of Christel Ambrosius and revealed that Mabel Smith knew a drug lord better than she had previously admitted.

Another important issue in his show was a found floppy-disk.

This disk contained detailed information from research on the Dutch secret service.

It turned out that the service observed the murdered politician Pim fortuyn, the service thought that he had sexual relations with Moroccan men.

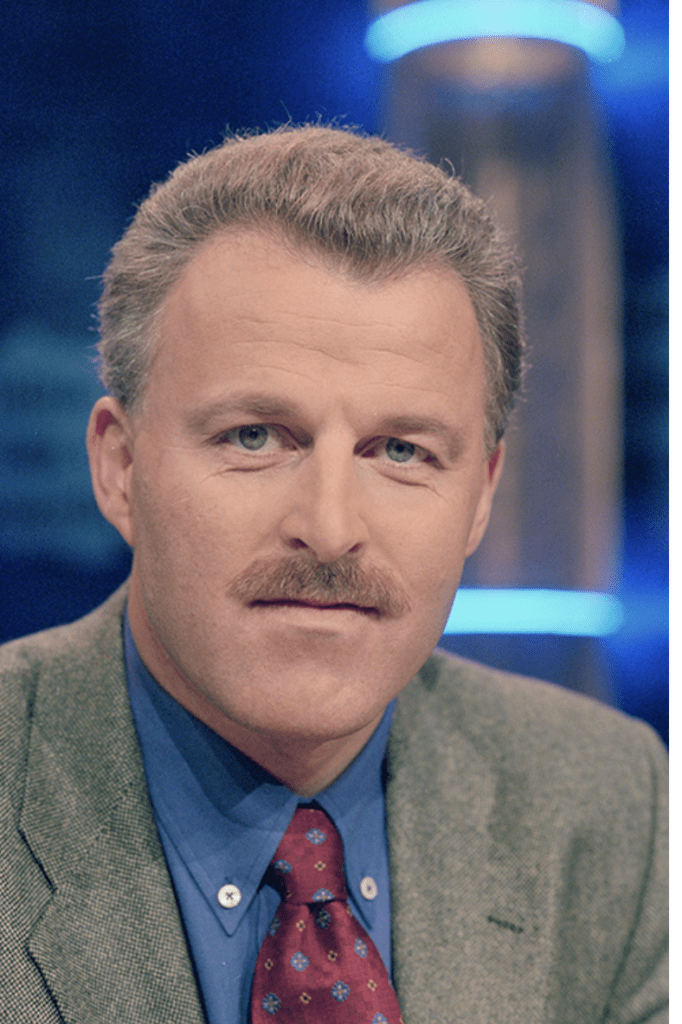

In 1983, De Vries followed the case of the Kidnapping of Freddy Heineken for the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf.

He attended proceedings and sometimes visited the hotels in France where the kidnappers Cor van de hout and Willem Hollandeer were being held under arrest.

Books & Film

Vries wrote two books based on his investigation.

The first was De zaak Heineken (The Heineken Case, 1983), released in the same year as the kidnapping.

This was followed by De ontvoering van Alfred Heineken (The Kidnapping of Alfred Heineken, 1987), a novel from the perspective of Cor can Hout based on interviews De Vries conducted with Hollandeer over a period of four weeks during his last hotel arrest in 1986.

The novel was later adapted as Kidnapping Freddy Heineken (2015) starring Anthony Hopkins.

Fame and misfortune

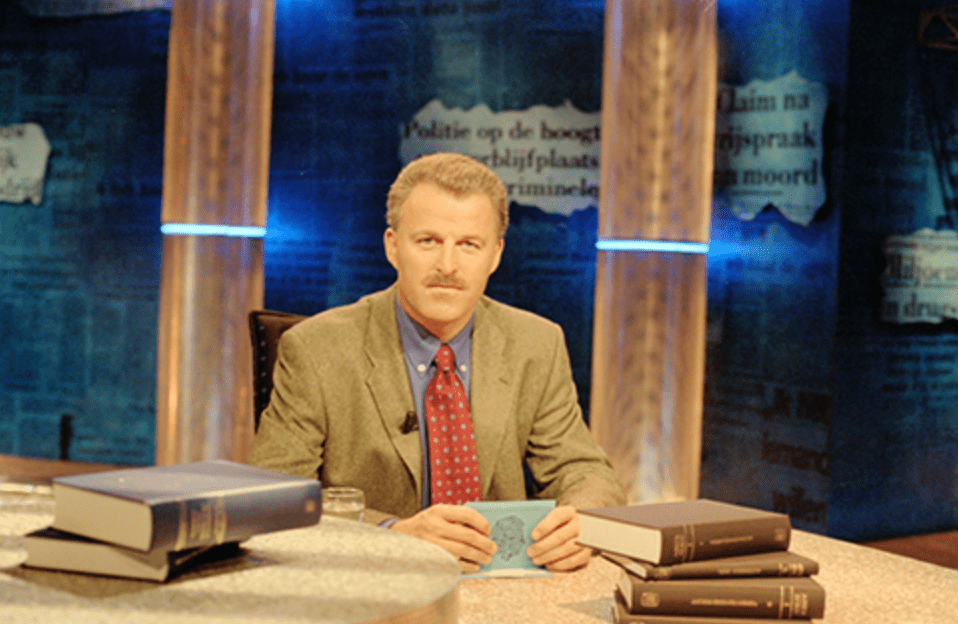

Peter R. de Vries (1956, Aalsmeer) has been the Netherlands’ most famous crime reporter for decades. As a writing journalist and television program host, De Vries has countless scoops to his name and has been at the base of many notorious affairs.

De Vries started his career immediately after high school and military service at the editorial office of De Telegraaf in The Hague, where he was hired as an “apprentice journalist” at the age of twenty.

In The Hague he investigated his first murder case and his predilection for crime journalism was born.

Thirty-five years later De Vries has investigated more than five hundred murder cases.

His TV program “Peter R. de Vries, crime reporter” has played a decisive role in solving more than a dozen murder cases.

He also solved disappearance cases and unmasked fraudsters, swindlers, extortionists, violent offenders and sex offenders.

With his years of investigation into the murder of Christel Ambrosius and the ‘Twee van Putten’ convicted for it, De Vries brought one of the biggest miscarriages of justice in our crime history to light.

His revelations about Princess Mabel and her secret contacts with the Amsterdam godfather Klaas Bruinsma shook the monarchy to its foundations.

The book written by De Vries about the kidnapping of Alfred Heineken has been the best-selling crime book in the Netherlands since it appeared in 1986 and is reprinted every year.

De Vries worked for De Telegraaf for almost ten years (1978-1987) and after a year was transferred from the editorial office in The Hague to the central editorial office in Amsterdam, where he devoted himself to writing crime stories.

There he was labeled a “crime reporter” by colleagues, an epithet that stuck to him for life.

Although in his twenties De Vries was for many years ‘the youngest reporter’ of De Telegraaf, he already made a name for himself with many revealing reports.

His final breakthrough came with the 1983 kidnapping of Alfred Heineken, which he covered for the newspaper.

After De Telegraaf, De Vries became chief editor for four years (1987 – 1991) of the weekly ‘Aktueel’, which he transformed into a crime magazine during that time.

In 1991, together with Jaap Jongbloed of the TROS, he founded the first television crime program: ‘Crime Time’, which was later renamed ‘Deadline’ and then changed to ‘Vermist’.

Between 1991 and 1995 De Vries had his own press agency, specialized in crime reports and columns, and worked for the Algemeen Dagblad, Panorama, Crime Time and other television programs.

In 1995 De Vries was asked to bring his own crime program to television for John de Mol Produkties.

This became ‘Peter R. de Vries, crime reporter’, which was continuously on television for seventeen years. fifteen of which with SBS6 and attracted attention far beyond our national borders with its spectacular reports.

Entrapment

De Vries was a pioneer in the field of the hidden camera and perfected this journalistic tool together with his crew.

The TV program acquired a reputation as the ‘louse in the fur’ of the justice system and the ‘tormentor of the underworld’.

Gradually the program specialized in so-called cold case investigations and child murders.

It also drew attention to miscarriages of justice and abuse of power by judicial authorities.

In 2002 he received an Academy Award in the Netherlands for his reports and role in solving a triple murder in Amsterdam that was about to expire.

The perpetrator was sentenced to life imprisonment.

The murder of Mr Kok

As I said at the beginning this isn’t the first time a journalist/ blogger has been shot in Amsterdam.

But the brutal shooting of ex criminal turned blogger Martin In 2016 was fatal.

He was killed outside a brothel.

Small World

Their stories intertwine too in a web that is intricate.

Martin grew up in the town of Volendam, in a place of wooden windmills and cheese markets.

As a teen, he and his father and brother sold eel at cafés in Amsterdam.

He would wear the traditional Volendammer garb: red shirt, baggy black pants, and clogs.

The work felt demeaning, and the patrons were condescending.

He started selling eel in bars popular with well-known criminals.

Kok moved on to the cocaine trade and quit his fishmonger job to work in smoky club coat rooms, which were good for meeting potential clients. It beat selling eels.

Kok was sardonic and charismatic—a class clown—but also tall, beefy, and imposing, with a streak of ruthlessness.

He was as disarming as he was dangerous, like Yogi Bear with a handgun.

According to a biography of him, in the summer of 1988, at the age of 21, he shot at an old schoolmate who had begun cutting into his business; several months later he got into a fight with a rival and smashed him in the head with a barstool.

The man died a day later, and Kok went to prison for five years, a not-unheard-of sentence in a country with fairly lenient sentencing terms.

During that prison term, Kok met a man named Holleeder who was in prison for the 1983 kidnapping of beer magnate Freddy Heineken, and the caper remains unmatched in the annals of Dutch crime; a huge ransom was paid and Holleeder went on the run in France before being caught.

In prison, Kok and Holleeder often ate lunch together, and Kok also befriended Cor van Hout, one of Holleeder’s accomplices in the Heineken kidnapping.

The modern drug trade in Holland stretches across the globe, much like those old trade routes, and the country’s crime blogging sites track this busy industry.

Today, Holland is a producer and consumer of synthetic drugs like ecstasy and the source for US-bound party drugs; the majority of drug offenses connected to heroin, cocaine, ecstasy, and amphetamines are related to possession.

With the drug trade comes violence. While many fewer murders are committed in the Netherlands than in the United States (0.55 per 100,000 people, compared with 5.3 for every 100,000 in the US), people pay much more attention to them, fed by the salacious details on the crime sites.

“Criminals are humans, like you and me,” says Wim van de Pol, who co-owns and edits (with van der Eng) Crimesite, a 14-year-old website operated by veteran journalists and editors that gets nearly 4 million pageviews a month.

“That’s what I like about crime reporting.

It’s a study in human ambition and human struggle.”

The many crime blogs cover—with varying degrees of journalistic rigor—the activities of criminals and “liquidations,” or assassinations.

False accusations are not unheard of.

And even the official newspapers, which tend to be rigorous in their sourcing and circumspect about what they publish, sometimes lean on the less-scrupulous digital publications for stories.

Kok joined this fraternity of crime bloggers in 2015 after being released from prison, when he moved to Amsterdam and launched Vlinderscrime.

It was easy enough: He was familiar with the crime blog scene, and he had many sources both free and incarcerated.

He also wanted to be part of the story himself; a blog could be a conduit to fame.

“I thought it would be fun to write about crime. I knew a lot about it, being a former criminal,” he told van der Eng, a former television journalist.

He was a bear poking other bears.

In 2014, Holleeder was charged with ordering the assassinations of multiple people, including his kidnapping coconspirator van Hout.

Kok, who was released from prison a few months later, used his media appearances to make fun of Holleeder.

“Holleeder is a crybaby, and he can’t stand being in prison,” Kok said on a daily talk show.

He mocked a reputed Dutch-Moroccan hit man who was arrested in Dublin, making fun of his many expensive watches and shoes.

“People warned him. ‘Be careful—you are insulting people,’” van der Eng says.

“He was insulting everyone, even Willem Holleeder, who was considered the biggest criminal in the Netherlands.

He thought of himself as a crime reporter, a journalist.

He was a shock blogger. It was without limits.”

Journalists enjoyed his company, and he enjoyed their validation.

But it was dangerous to be too close to him; a bullet meant for Kok might stray.

Journalists who met with him for dinner would not let him pay their bills, fearing that it would lead to discomfiting moral debts.

“He managed to get a lot of attention.

He was successful at earning money without any more criminal activities.

People liked him,” van der Eng told me.

He loved his notoriety.

Despite his pleasure in taunting drug dealers and killers, he did eventually develop some instinct for self-preservation.

“Before the bomb and the shooting, I welcomed everything and everyone, but I have become more careful,” he told van der Eng in 2016.

He described getting a call from someone who wanted to give him information about an assassination. “It didn’t feel right, so I declined his invitation.”

His newfound instincts only went so far: At one point, Kok reportedly called the leader of a gang he had written about and dared them to come and find him.

He gave the address of the house and hung up and waited.

No one ever came, strengthening his illusion of invincibility.

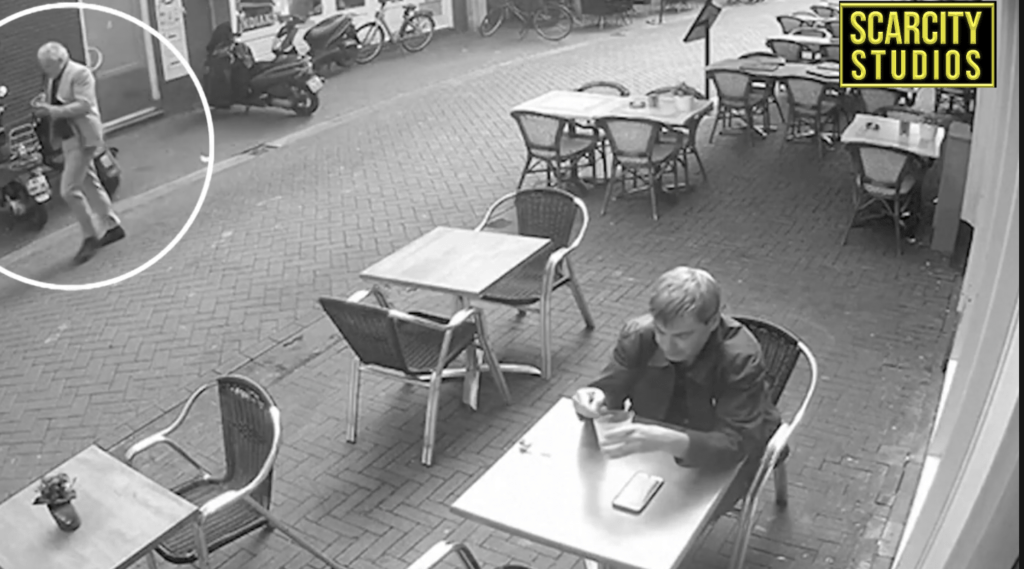

On December 8, 2016, after unwittingly surviving an assassination attempt on that Amsterdam sidewalk, Kok went to one of his favorite sex clubs, just outside Amsterdam.

A photo shows him there, lounging on a bed in black underpants.

A pink neon light glowing behind him, he gives a double thumbs up to the camera.

He left the club around 11:20, and surveillance footage shows the lights on a Volkswagen Polo in the club parking lot wink to life as he walks out the door.

Kok crosses over to the car and gets in.

From the bushes an assassin emerges.

Maybe it’s the same gunman from earlier in the evening on the sidewalk.

Maybe not. This time the gun doesn’t jam: The man fires into the driver’s side window and retreats.

Months after his funeral, on a February day overcast and spittly with rain, I visited his grave at the Vredenhof Cemetery, in an industrial part of Amsterdam.

A caretaker directed me down a path toward the very back of the cemetery.

Decorated with a headshot and butterflies, the grave marker was much smaller than those of the two men he is buried next to: Gijs Van Dam Jr., the son of a major distributor of hashish, and Kok’s friend Cor Van Hout.

Some journalists have tentatively tied Kok’s murder to the elusive criminal collective known as 26Koper (a “murder service on wheels,” according to one headline Kok wrote).

Maybe they killed him.

Maybe a hit was ordered by someone like the supposed hit man he had mocked.

Plenty of people had reason to be mad at him.

Whoever killed him, no one in the crime blogging community was surprised.

And Kok, his colleagues said, would have loved the attention.

“There was one thing he was aiming for,” Vico Olling, a journalist at the Dutch magazine Panorama, tells me.

“That was his death.”