Police are investigating reports of shots fired overnight in the Ballymagroarty area of Londonderry.

It comes as a video was circulated on social media showing a masked man, armed with a pistol, firing shots into the air. The gunman was flanked by other males believed to be members of the INLA’s Derry brigade holding flags before the shots rang out.

Shortly after the incident, residents took to social media to report how PSNI armed response officers had arrived in the area.

A short time later police were alerted to a suspicious object in the Racecourse Road area of the City. The road was closed overnight as a major security operation was put in place. The object was later declared an elaborate hoax.

Police have linked the security alert to the hijacking of a silver-coloured Mitsubishi Outlander on Ballyarnett Road at around 9.30pm.

UUP leader Doug Beattie branded the masked men “ghouls” and “embarrassing freaks.”

The original upload to YouTube was removed on the basis of their rules on “criminal organisations”

Their statement reads

“Content intended to praise, promote or aid violent criminal organisations is not allowed on YouTube. These organisations are not allowed to use YouTube for any purpose, including recruitment. If you find content that violates this policy, report it.”

This video is a factually accurate and historically supported and sourced with no bias or condoning of any violence.

Thank you for watching and supporting.

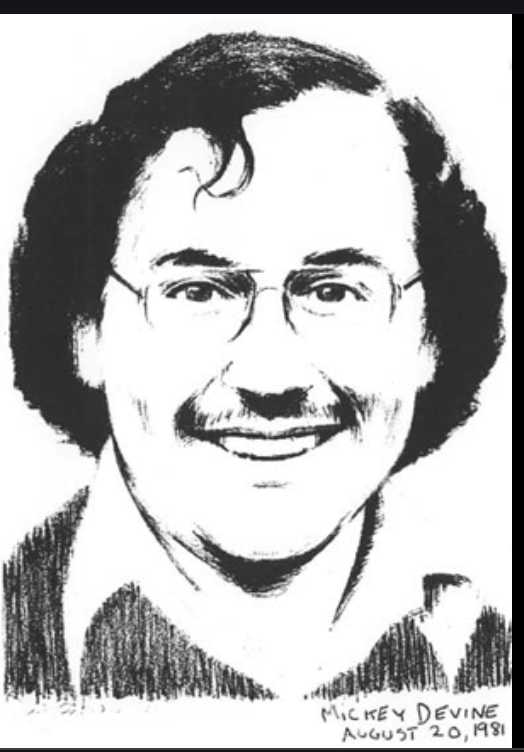

Devine, who came from the Creggan area of the city, died at the Maze prison on August 20, 1981 aged 27 – 60 days after he joined the Hunger Strike.

He joined the INLA in 1974. Two years later, he was arrested after an arms raid in Donegal. He was sentenced to 12 years in jail for possession.

Recently in Northern Ireland police made a specialist paramilitary crime task force has been helping police with a “significant escalation” of shooting incidents in the Coleraine area.

After no shooting incidents were recorded in the Causeway Coast and Glens Borough Council area in 2019, there were 14 in the area last year.

That was the second highest number in NI in 2020, behind only Belfast (16).

“It’s an extremely worrying development and I’ve brought in additional resources,” Supt Ian Magee said.

The PSNI district commander said local paramilitary groups are “lines of inquiry that teams are actively following”.

The Paramilitary Crime Task Force (PCTF) was established in 2017 to help tackle organised crime by paramilitary groups.

It consists of PSNI officers, staff from the National Crime Agency (NCA) and customs officers.

Bonfires

A example of sectarian tension is seen through the bonfires.

The police are reviewing evidence after “offensive and distasteful” material appeared on a Londonderry bonfire, a senior officer has said.

A bonfire in Meenan Square in the Bogside on Sunday had banners “making threats towards police officers and a member of the public,” police said.

Politicians have condemned the incident, with some referring to it as a hate crime and “disgraceful”.

“An evidence gathering operation was in place,” PSNI Ch Supt Darrin Jones said.

He said if any offences were detected, a full police investigation would be carried out.

One of the posters referenced the murder of Catholic PSNI officer Ronan Kerr, killed when dissident republicans fitted a booby-trapped bomb to his car in Omagh, County Tyrone, in 2011.

Another made reference to PSNI Chief Constable Simon Byrne.

The Police Federation for Northern Ireland said the incident was a “deep insult” to the memory of Ronan Kerr and an “appalling indictment of some sections of our society”.

“It is designed to intimidate and is deeply insulting to the vast majority of our society who support policing,” said the federation’s chair Mark Lindsay.

He called on people in positions of responsibility to help “eradicate this abhorrent practice”.

The SDLP’s Brian Tierney, who sits on Derry City and Strabane District Council’s bonfire working group, said some of the banners burnt on Sunday night were “disappointing”.

“We need to make young people understand that burning a flag or banner is not part of your tradition and point out just how offensive that can be to the other side of the community, ” Mr Tierney told BBC Radio Foyle.

Bonfires on 15 August are traditional in some nationalist parts of Northern Ireland to mark the Catholic Feast of the Assumption.

Good Friday agreement

The provisional wing of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) has disarmed after a 36-year armed campaign for a unified Irish state, according to a Sept. 26 report by independent international observers.

Canadian General John de Chastelain, head of the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning (IICD), was invited to monitor IRA members’ Sept. 25 voluntary destruction of guns, ammunition, and explosives. The commission report found the disarmament effort to be complete.

“We believe with confidence that the arms decommissioned represent the totality of the IRA arsenal,” said the commissioners in their Sept. 26 statement.

The British and Irish governments established the IICD in 1997 to independently monitor the disarmament of paramilitary groups on each side of the Northern Ireland conflict.

British Prime Minister Tony Blair, whose administration has worked over the last few years to bring the conflict in Northern Ireland to resolution, expressed his confidence in the commission’s findings.

“Successive British governments have sought final and complete decommissioning by the IRA for over 10 years…. Today it is finally accomplished,” said Blair.

According to commission press statements, the number of weapons destroyed corresponded to British and Irish government estimates.

De Chastelain suggested in his Sept. 26 press conference that the amount correlated to a Jane’s Intelligence Review estimate of the IRA arsenal, which included 1,000 rifles, two metric tons of Semtex explosive, seven surface-to-air missiles, and two-dozen heavy machine guns.

Commission members noted in the Sept. 26 statement that there is further disarmament work to be done.

“It remains for us to address the arms of the loyalist paramilitary groups, as well as other paramilitary groups, when these groups are prepared to cooperate with us in doing so.”

The IRA was by far the largest existing Irish Republican paramilitary group, leaving only two small splinter groups still armed.

MICKY DEVINE

Died August 20th, 1981

A typical Derry lad

Twenty-seven-year-old Micky Devine, from the Creggan in Derry city, was the third INLA Volunteer to join the H-Block hunger strike to the death.

Micky Devine took over as O/C of the INLA blanket men in March when the then O/C, Patsy O’Hara, joined the hunger strike but he retained this leadership post when he joined the hunger strike himself.

Known as ‘Red Micky’, his nickname stemmed from his ginger hair rather than his political complexion, although he was most definitely a republican socialist.

The story of Micky Devine is not one of a republican ‘super-hero’ but of a typical Derry lad whose family suffered all of the ills of sectarian and class discrimination inflicted upon the Catholic working-class of that city: poor housing, unemployment and lack of opportunity.

Micky himself had a rough life.

His father died when Micky was a young lad; he found his mother dead when he was only a teenager; married young, his marriage ended in separation; he underwent four years of suffering ‘on the blanket’ in the H-Blocks; and, finally, the torture of hunger-strike.

Unusually for a young Derry nationalist, because of his family’s tragic history (unconnected with ‘the troubles’), Micky was not part of an extended family, and his only close relatives were his sister Margaret, seven years his elder, and now aged 34, and her husband, Frank McCauley, aged 36.

CAMP

Michael James Devine was born on May 26th, 1954 in the Springtown camp, on the outskirts of Derry city, a former American army base from the Second World War, which Micky himself described as “the slum to end all slums”.

Hundreds of families – 99% (unemployed) Catholics, because of Derry corporation’s sectarian housing policy – lived, or rather existed, in huts, which were not kept in any decent state of repair by the corporation.

One of Micky’s earliest memories was of lying in a bed covered in old coats to keep the rain off the bed.

His sister, Margaret, recalls that the huts were “okay” during the summer, but they leaked, and the rest of the year they were cold and damp.

Micky’s parents, Patrick and Elizabeth, both from Derry city, had got married in late 1945 shortly after the end of the Second World War, during which Patrick had served in the British merchant navy.

He was a coalman by trade, but was unemployed for years.

At first Patrick and Elizabeth lived with the latter’s mother in Ardmore, a village near Derry, where Margaret was born in 1947. In early 1948 the family moved to Springtown where Micky was born in May 1954.

Although Springtown was meant to provide only temporary accommodation, official lethargy and sectarianism dictated that such inadequate housing was good enough for Catholics and it was not until the early ‘sixties that the camp was closed.

BLOW

During the ‘fifties, the Creggan was built as a new Catholic ghetto, but it was 1960 before the Devines got their new home in Creggan, on the Circular Road. Micky had an unremarkable, but reasonably happy childhood. He went to Holy Child primary school in Creggan.

At the age of eleven Micky started at St. Joseph’s secondary school in Creggan, which he was to attend until he was fifteen.

But soon the first sad blow befell him. On Christmas eve 1965, when Micky was aged only eleven, his father fell ill; and six weeks later, in February 1966, his father, who was only in his forties, died of leukaemia.

Micky had been very close to his father and his premature death left Micky heartbroken.

Five months later, in July 1966, his sister Margaret left home to get married, whilst Micky remained in the Devines’ Circular Road home with his mother and granny.

At school Micky was an average pupil, and had no notable interests.

STONING

The first civil rights march in Derry took place on October 5th, 1968, when the sectarian RUC batoned several hundred protesters at Duke Street. Recalling that day, Micky, who was then only fourteen wrote:

“Like every other young person in Derry my whole way of thinking was tossed upside down by the events of October 5th, 1968. I didn’t even know there was a civil rights march. I saw it on television.

“But that night I was down the town smashing shop windows and stoning the RUC. Overnight I developed an intense hatred of the RUC. As a child I had always known not to talk to them, or to have anything to do with them, but this was different

“Within a month everyone was a political activist. I had never had a political thought in my life, but now we talked of nothing else. I was by no means politically aware but the speed of events gave me a quick education.”

TENSION

After the infamous loyalist attack on civil rights marchers in nearby Burntollet, in January 1969, tension mounted in Derry through 1969 until the August 12th riots, when Orangemen – Apprentice Boys and the RUC – attacked the Bogside, meeting effective resistance, in the ‘Battle of the Bogside’. On two occasions in 1969 Micky ended up at the wrong end of an RUC baton, and consequently in hospital.

That summer Micky left school.

Always keen to improve himself, he got a job as a shop assistant and over the next three years worked his way up the local ladder: from Hill’s furniture store on the Strand Road, to Sloan’s store in Shipquay Street, and finally to Austin’s furniture store in the Diamond.

British troops had arrived in August 1969, in the wake of the ‘Battle of the Bogside’. ‘Free Derry’ was maintained more by agreement with the British army than by physical force, but of course there were barricades, and Micky was one of the volunteers manning them.

INVOLVED

At that time, and during 1970 and 1971, Micky became involved in the civil rights movement, and with the local (uniquely militant) Labour Party and the Young Socialists.

The already strained relationship between British troops and the nationalist people of Derry steadily deteriorated – reinforced by news from elsewhere, especially Belfast – culminating with the shooting dead by the British army of two unarmed civilians, Seamus Cusack and Desmond Beattie, in July of 1971, and with internment in August. Micky, by this time seventeen years of age, and also politically maturing, had joined the ‘Officials’, also known as the ‘Sticks’.

He became a member of the James Connolly ‘Republican Club’ and then, shortly after internment, a member of the Derry Brigade of the ‘Official IRA’.

‘Free Derry’ had become known by that name after the successful defence of the Bog side in August 1969, but it really became ‘Free Derry’, in the form of concrete barricades etc., from internment day. Micky was amongst those armed volunteers who manned the barricades

Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday, January 30th, 1972, when British Paratroopers shot dead thirteen unarmed civil rights demonstrators in Derry (a fourteenth died later from wounds received), was a turning point for Micky.

From then there was no turning back on his republican commitment and he gradually lost interest in his work, and he was to become a full-time political and military activist.

TRAUMA

Micky experienced the trauma of Bloody Sunday at first hand.

He was on that fateful march with his brother-in-law, Frank, who recalls: “When the shooting started we ran, like everybody else, and when it was over we saw all the bodies being lifted.”

The slaughter confirmed to Micky that it was more than time to start shooting back.

“How” he would ask, “can you sit back and watch while your own Derry men are shot down like dogs?”

Micky had written: “I will never forget standing in the Creggan chapel staring at the brown wooden boxes.

We mourned, and Ireland mourned with us.

“That sight more than anything convinced me that there will never be peace in Ireland while Britain remains. When I looked at those coffins I developed a commitment to the republican cause that I have never lost.”

From around this time, until May when the ‘Official IRA’ leadership declared a unilateral ceasefire (unpopular with their Derry Volunteers), Micky was involved not only in defensive operations but in various gun attacks against British troops.

Micky’s commitment and courage had shone through, but no more so than in the case of scores of other Derry youths, flung into adulthood and warfare by a British army of occupation.

TRAGIC

In September, 1972, came the second tragic loss in Micky’s family life.

He came home one day to find his mother dead on the settee with his granny unsuccessfully trying to revive her.

His mother had died of a brain tumour, totally unexpectedly, at the age of forty-five. Doctors said it had taken her just three minutes to die. Micky, then aged eighteen, suffered a tremendous shock from this blow, and it took him many months to come to terms with his grief.

Through 1973, Micky remained connected with the ‘Sticks’, although increasingly disillusioned by their openly reformist path. He came to refer to the ‘Sticks’ as “fireside republicans”, and was highly critical of them for not being active enough.

Towards the end of that year, Micky, then aged nineteen, got married. His wife, Margaret, was only seventeen. They lived in Ranmore Drive in Creggan and had two children: Michael, now aged seven and Louise, now aged five.

Micky and his wife had since separated.

In late 1974, virtually all the ‘Sticks’ in Derry, including Micky, joined the newly formed IRSP, as did some who had dropped out over the years.

And Micky necessarily became a founder member of the PLA (People’s Liberation Army), formed to defend the IRSP from murderous attacks by their former comrades in the sticks.

In early 1975, Micky became a founder member of the INLA (Irish National Liberation Army) formed for offensive operational purposes out of the PLA.

The months ahead were bad times for the IRSP, relatively isolated, and to suffer a strength-sapping split when Bernadette McAliskey left, taking with her a number of activists who formed the ISP (Independent Socialist Party), since deceased.

They were also difficult months for the fledgling INLA, suffering from a crippling lack of weaponry and funds. Weakness which led them into raids for both as their primary actions, and rendered them almost unable to operate against the Brits.

Micky was eventually arrested on the Creggan. In the evening of September 20th, 1976, after an arms raid earlier that day on a private weaponry, in Lifford, County Donegal, from which the INLA commandeered several rifles and shotguns, and three thousand rounds of ammunition.

ARRESTED

Micky was arrested with Desmond Walmsley from Shantallow, and John Cassidy from Rosemount.

Micky was held and interrogated for three days in Derry’s Stand Road barracks, before being transported in Crumlin Road jail in Belfast where he spent nine months on remand.

He was sentenced to twelve years imprisonment on June 20th, 1977, and immediately embarked on the blanket protest. He was in H5-Block until March of this year when the hunger strike began and when the ‘no-wash, no slop-out’ protest ended, whereupon he was moved with others in his wing to H6-Block.

Like others incarcerated within the H-Blocks, suffering daily abuse and inhuman and degrading treatment, Micky realised – soon after he joined the blanket protest – that eventually it would come to a hunger strike, and, for him, the sooner the better.

SEVENTH

On Sunday, June 21st, this year, he completed his fourth year on the blanket, and the following day he joined Joe McDonnell, Kieran Doherty, Kevin Lynch, Martin Hurson, Thomas McElwee and Paddy Quinn on hunger strike.

He became the seventh man in a weekly build-up from a four-strong hunger strike team to eight-strong. He was moved to the prison hospital on Wednesday, July 15th, his twenty fourth day on hunger strike.

With the 50 % remission available to conforming prisoners, Micky would have been due out of jail next September.

As it was, because of his principled republican rejection of the criminal tag he chose to fight and face death.

Micky died at 7.50 am on Thursday, August 201h, as nationalist voters in Fermanagh/South Tyrone were beginning to make their way to the polling booths to elect Owen Carron, a member of parliament for the constituency, in a demonstration – for the second time in less than five months – of their support for the prisoners’ demands.

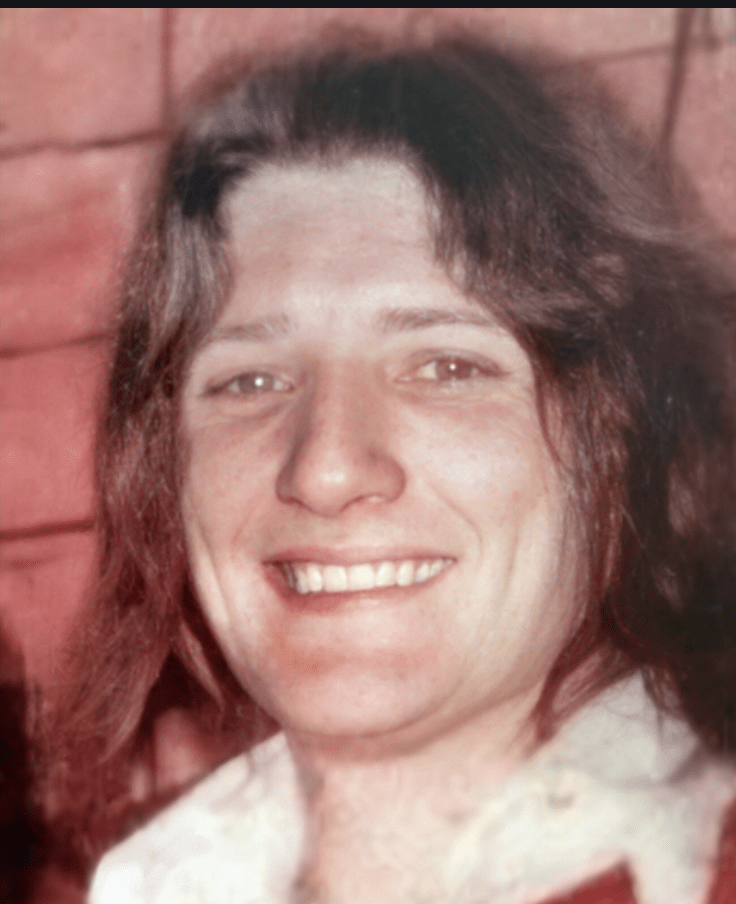

Bobby Sands

Died May 5th, 1981

The revolutionary spirit of freedom

Bobby Sands, Roibeard Gearóid Ó Seachnasaigh, was born in 1954 in Rathcoole, a predominantly loyalist district of north Belfast. His twenty-seventh birthday fell on the ninth day of his sixty-six-day hunger strike.

His sisters Marcella, one year younger, and Bernadette, were born in April 1955 and November 1958, respectively. All three lived their early years at Abbots Cross in the Newtownabbey area of north Belfast.

A second son, John, now nineteen, was born to their parents John and Rosaleen, now both aged 57, in June 1962.

The sectarian realities of ghetto life materialised early in Bobby’s life when at the age of ten his family were forced to move home owing to loyalist intimidation even as early as 1962.

Bobby recalled his mother speaking of the troubled times which occurred during her childhood; ‘Although I never really understood what internment was or who the ‘Specials’ were, I grew to regard them as symbols of evil ‘.

Of this time Bobby himself later wrote: ”I was only a working-class boy from a Nationalist ghetto, but it is repression that creates the revolutionary spirit of freedom.

I shall not settle until I achieve liberation of my country, until Ireland becomes a sovereign, independent socialist republic. ”

When Bobby was sixteen years old he started work as an apprentice coach builder and joined the National Union of Vehicle Builders and the ATGWU. In an article printed in ‘An Phoblacht/Republican News’ on April 4th, 1981, Bobby recalled: ”Starting work, although frightening at first became alright, especially with the reward at the end of the week. Dances and clothes, girls and a few shillings to spend, opened up a whole new world to me.”

Bobby’s background, experiences and ambitions did not differ greatly from that of the average ghetto youth.

Then came 1968 and the events which were to change his life. Bobby had served two years of his apprenticeship when he was intimidated out of his job.

His sister Bernadette recalls: “Bobby went to work one morning and these fellows were standing there cleaning guns. One fellow said to him, ‘Do you see these here, well if you don’t go you’ll get this’ then Bobby also found a note in his lunch-box telling him to get out.”

In June 1972, the family were intimidated out of their home in Doonbeg Drive, Rathcoole and moved into the newly built Twinbrook estate on the fringe of nationalist West Belfast.

Bernadette again recalled: We had suffered intimidation for about eighteen months before we were actually put out. We had always been used to having Protestant friends. Bobby had gone around with Catholics and Protestants, but it ended up when everything erupted, that the friends he went about with for years were the same ones who helped to put his family out of their home.

As well as being intimidated out of his job and his home being under threat Bobby also suffered personal attacks from the loyalists.

At eighteen Bobby joined the Republican Movement. Bernadette says: .. ‘he was just at the age when he was beginning to become aware of things happening around him. He more or less just said right, this is where I’m going to take up.

A couple of his cousins had been arrested and interned. Booby felt that he should get involved and start doing something. ‘

Bobby himself wrote. “My life now centered around sleepless nights and stand-bys dodging the Brits and calming nerves to go out on operations.

But the people stood by us. The people not only opened the doors of their homes to lend us a hand but they opened their hearts to us. I learned that without the people we could not survive and I knew that I owed them everything.

In October 1972, he was arrested. Four handguns were found in a house he was staying in and he was charged with possession.

He spent the next three years in the cages of Long Kesh where he had political prisoner status.

During this time Bobby read widely and taught himself Irish which he was later to teach the other blanket men in the H-Blocks.

Released in 1976 Bobby returned to his family in Twinbrook.

He reported back to his local unit and straight back into the continuing struggle: ‘Quite a lot of things had changed some parts of the ghettos had completely disappeared and others were in the process of being removed.

The war was still forging ahead although tactics and strategy had changed.

The British government was now seeking to ‘Ulsterise’ the war which included the attempted criminalisation of the IRA and attempted normalisation of the war situation.’

Bobby set himself to work tackling the social issues which affected the Twinbrook area.

Here he became a community activist. According to Bernadette, ‘When he got out of jail that first time our estate had no Green Cross, no Sinn Fein, nor anything like that. He was involved in the Tenants’ Association… He got the black taxis to run to Twinbrook because the bus service at that time was inadequate.

It got to the stage where people were coming to the door looking for Bobby to put up ramps on the roads in case cars were going too fast and would knock the children down.’

Within six months Bobby was arrested again.

There had been a bomb attack on the Balmoral Furniture Company at Dunmurry, followed by a gun-battle in which two men were wounded.

Bobby was in a car near the scene with three other young men.

The RUC captured them and found a revolver in the car.

The six men were taken to Castlereagh and were subjected to brutal interrogations for six days.

Bobby refused to answer any questions during his interrogation, except his name, age and address.

In a ninety-six verse poem written in 1980, entitled ‘The Crime of Castlereagh’, Bobby tells of his experiences in Castlereagh and his fears and thoughts at the time.

They came and came their job the same

In relays N’er they stopped.

‘Just sign the line!’ They shrieked each time

And beat me ’till I dropped.

They tortured me quite viciously

They threw me through the air.

It got so bad it seemed I had

Been beat beyond repair.

The days expired and no one tired,

Except of course the prey,

And knew they well that time would tell

Each dirty trick they laid on thick

For no one heard or saw,

Who dares to say in Castlereagh

The ‘police’ would break the law!

He was held on remand for eleven months until his trial in September 1977. As at his previous trial he refused to recognise the court.

The judge admitted there was no evidence to link Bobby, or the other three young men with him, to the bombing. So the four of them were sentenced to fourteen years each for possession of the one revolver.

Bobby spent the first twenty-two days of his sentence in solitary confinement, ‘on the boards’ in Crumlin Road jail. For fifteen of those days he was completely naked.

He was moved to the H-Blocks and joined the blanket protest.

He began to write for Republican News and then after February 1979 for the newly-merged An Phobhacht/Republican News under the pen-name, ‘Marcella’, his sister’s name.

His articles and letters, in minute handwriting, like all communications from the H-Blocks, were smuggled out on tiny pieces of toilet paper.

He wrote: ‘The days were long and lonely.

The sudden and total deprivation of such basic human necessities as exercise and fresh air, association with other people, my own clothes and things like newspapers, radio, cigarettes books and a host of other things, made my life very hard.’

Bobby became PRO for the blanket men and was in constant confrontation with the prison authorities which resulted in several spells of solitary confinement.

In the H-Blocks, beatings, long periods in the punishment cells, starvation diets and torture were commonplace as the prison authorities, with the full knowledge and consent of the British administration, imposed a harsh and brutal regime on the prisoners in their attempts to break the prisoners’ resistance to criminalisation.

The H-Blocks became the battlefield in which the republican spirit of resistance met head-on all the inhumanities that the British could perpetrate.

The republican spirit prevailed and in April 1978 in protest against systematic ill-treatment when they went to the toilets or got showered, the H-Block prisoners refused to wash or slop-out.

They were joined in this no-wash protest by the women in Armagh jail in February 1980 when they were subjected to similar harassment.

On October 27th, 1980, following the breakdown of talks between British direct ruler in the North, Humphrey Atkins, and Cardinal O Fiaich, the Irish Catholic primate, seven prisoners in the H-Blocks began a hunger strike.

Bobby volunteered for the fast but instead he succeeded, as O/C, Brendan Hughes, who went on hunger-strike.

During the hunger-strike he was given political recognition by the prison authorities.

The day after a senior British official visited the hunger-strikers, Bobby was brought half a mile in a prison van from H3 to the prison hospital to visit them.

Subsequently he was allowed several meetings with Brendan Hughes.

He was not involved in the decision to end the hunger-strike which was taken by the seven men alone.

But later that night he was taken to meet them and was allowed to visit republican prison leaders in H-Blocks 4, 5 and 6.

On December 19th, 1980, Bobby issued a statement that the prisoners would not wear prison-issue clothing nor do prison work.

He then began negotiations with the prison governor, Stanley Hilditch, for a step-by-step de-escalation of the protest.

But the prisoners’ efforts were rebuffed by the authorities: ‘We discovered that our good will and flexibility were in vain,’ wrote Bobby.

It was made abundantly clear during one of my co-operation’ meetings with prison officials that strict conformity was required. which in essence meant acceptance of criminal status.

In the H-Blocks the British saw the opportunity to defeat the IRA by criminalising Irish freedom fighters but the blanketmen, perhaps more than those on the outside, appreciated before anyone else the grave repercussions, and so they fought.

Bobby volunteered to lead the new hunger strike. He saw it as a microcosm of the way the Brits were treating Ireland historically and presently, Bobby realised that someone would have to die to win political status.

He insisted on starting two weeks in front of the others so that perhaps his death could secure the five demands and save their lives.

For the first seventeen days of the hunger strike Bobby kept a secret diary in which he wrote his thoughts and views, mostly in English but occasionally breaking into Gaelic.

He had no fear of death and saw the hunger-strike as something much larger than the five demands and as having major repercussions for British rule in Ireland.

The diary was written on toilet paper in biro pen and had to be hidden, mostly carried inside Bobby’s own body. During those first seventeen days Bobby lost a total of sixteen pounds weight and on Monday, March 23rd, he was moved to the prison hospital.

On March 30th, he was nominated as candidate for the Fermanagh and South Tyrone by-election caused by the sudden death of Frank Maguire, an independent MP who supported the prisoners’ cause.

The next morning, day thirty-one, of his hunger-strike, he was visited by Owen Carron who acted as his election agent.

Owen told of that first visit ‘Instead of meeting that young man of the poster with long hair and a fresh face, even at that time when Bobby wasn’t too bad he was radically changed.

He was very thin and bony and his hair was cut short.’

Bobby had no illusions with regard to his election victory.

His reaction was not one of over-optimism. After the result was announced Owen visited Bobby. “He had already heard the result on the radio.

He was in good form alright but he always used to keep saying, ‘In my position you can’t afford to be optimistic.’ In other words, he didn’t take it that because he’d won an election that his life would be saved.

He thought that the Brits would need their pound of flesh.

I think he was always working on the premise that he would have to die.”

At 1.17 a.m. on Tuesday, May 5th, having completed sixty-five days on hunger-strike, Bobby Sands MP, died in the H-Block prison hospital at Long Kesh. Bobby was a truly unique person whose loss is great and immeasurable.

In his own words: “of course can be murdered but I remain what I am, a political POW and no-one, not even the British, can change that.”